Some years ago, I joined a conference hosted by one of Silicon Valley’s top venture capitalists. It was the kind of event I knew well, when startup CEOs gather together to share market insights and receive pearls of wisdom from those with more experience. Once upon a time, I was one of those CEOs; now I had been invited to discuss my work on wilful blindness.

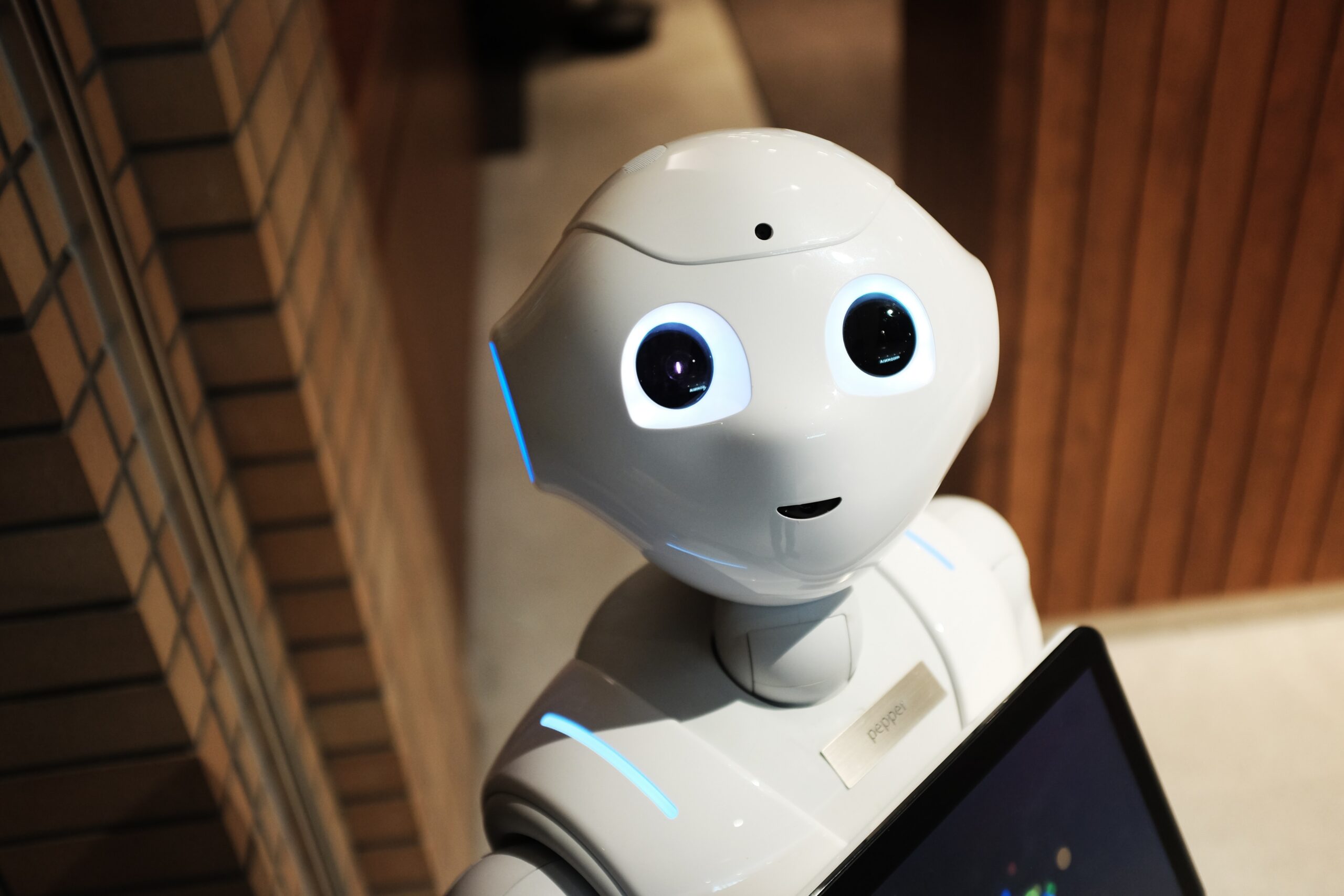

I remember little about the conference beyond its opening: “There is nothing wrong with medicine that getting rid of doctors won’t fix. There is nothing wrong with education that getting rid of teachers won’t fix. There’s nothing wrong with the legal system that getting rid of lawyers won’t fix.” These aggressive statements of inevitability struck a new and hostile tone: in a future stand-off between technology and people, it was human beings who would have to surrender.

Underlying this messianic message lay the belief that, with enough data and the right technology, the future could be impeccably predicted and planned, with all the contradictions, inconvenience and friction of life magically erased. People – random, messy, irrational – are the problem but tech is the solution.

Connectedness and complexity

But that faith in prediction has since faced many profound challenges. Sexual exploitation isn’t news yet #MeToo came as a surprise. American police have been shooting black citizens for decades, but BlackLivesMatter spread around the world with a ferocity that surprised many. A pandemic, wars, fractured supply chains, energy crises, food insecurity, mass migration, inflation: all have been unforeseen, hard to explain and not readily solved by software. At work have been a dense skein of forces defying forecasts. While we may hope and talk about returning to normal, the extreme events of the last three years are a manifestation of a deep change that has gone mostly unremarked by executives and legislators.

Over the last 30 to 40 years, our world has shifted from being generally complicated to being highly complex. Complicated environments are linear, follow rules and are predictable. They’re optimized for routine and efficiency and similar problems can be solved in similar ways. This is the context in which traditional management has evolved and where technology has delivered huge returns.

But the advent of globalization, coupled with pervasive communications, has rendered much of life complex: non-linear and fluid, where there may be patterns, but they don’t repeat predictably, and very small effects can produce disproportionate impacts. More forces may be at work together than we can see and problems may look simple while the relationship between cause and effect remains ambiguous. Connectedness confers benefits but also ushers in a myriad of unexpected consequences.

“Mightn’t enough data and analysis give us the ability to see the future and plan efficiently? But for data to yield reliable predictions, it must fit proven models – and such models have proved elusive.”

How can we predict the unpredictable?

Against this backdrop of turbulence, data and technology are held up as panaceas. Mightn’t enough data and analysis give us the ability to see the future and plan efficiently? But for data to yield reliable predictions, it must fit proven models – and such models have proved elusive. Wars and pandemics have been with us throughout human history – yet we have predictable models for neither. Academic researchers tried, using massive datasets, machine learning and neural networks, to identify patterns that predict war, but they couldn’t. States and political causes change shape too frequently, the onset, location and timing of conflict remains too ambiguous to generate reliable patterns, and violence has too many predictors. The same problem applies to pandemics: we know they will keep coming yet there is no profile for them. We don’t know when the next one will start, or where, or what the pathogen will be. Or, as epidemiologists like to joke: if you’ve seen one pandemic, you’ve seen…one pandemic.

Such complexity explains why experts in forecasting now show that if you frame your forecasts with probabilities, regularly consult a broad range of information sources, update your estimates and always analyze your success or failure, then the furthest out you can see with a useful degree of accuracy is around 400 days. If, like most of us, you are less punctilious, the window for accurate prediction is closer to 150 days. So forecasting, the anchor of business strategy, won’t deliver the frictionless certainties once imagined.

“In an age of uncertainty, imagination, creativity and human adaptability become mission-critical skills to deal with the unprecedented and unexpected.”

This has two consequences. In an environment where so much defies forecasting, efficiency won’t just not help us; over-fitting to a tight model undermines our capacity to respond and adjust. And in an age of uncertainty, imagination, creativity and human adaptability become mission-critical skills to deal with the unprecedented and unexpected.

Technology and humans playing to each other’s strengths

So the real challenge isn’t to win some imagined war between people and technology. It is to find the most productive ways to collaborate, playing to the strengths of each. One example is the founding of CEPI, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, launched after the 2014 – 2016 ebola outbreak when, for the first time ever, a vaccine trial had ended an epidemic. Why not, scientists wondered, develop vaccines now for likely diseases with pandemic potential? It’s not efficient – some vaccines won’t work, some diseases might never erupt into epidemics – but it provides options, gets ahead of the threat and doesn’t depend on a single technological approach. Of the first six candidates that CEPI chose, corona viruses was one and Moderna an early investment. But epidemic responsiveness also requires people on the ground; you don’t, they say, want to be exchanging business cards in a crisis. So CEPI started early, building alliances of trust and generosity. This accelerated information when, sooner than expected, a pandemic was upon us.

A more mundane example of creative collaboration between people and technology comes from a Dutch company, Buurtzorg. In the Netherlands, much healthcare depends on homecare nursing. Hospitals are expensive and dangerous places, and people typically recover faster in their own surroundings. In the past, the insurers used predictive models to maximize efficiency: assigning contracts and rotas, detailing the nurses’ work by the minute. The process functioned but was expensive and everyone hated it: the patients felt like commodities and the nurses’ professional judgment had been outsourced to the scheduling software.

“What was standard and repeatable was optimized with software; what was non-standard and unpredictable was better addressed with professional human judgment.”

One nurse, Jos de Blok, spotted the mistake. The single system was, in fact, two. Assigning nurses and issuing insurance invoices was a complicated process, easily improved by technology. But looking after patients was complex: no two patients recover from the same procedure at the same rate. De Blok proposed an experiment: let the nurses work as a team, using their professional judgment to decide how best to care for the patient. Recording details of their work onto iPads allowed the administrators to issue invoices and the nurses to share information. The results were decisive: the cost of the service fell by 30 percent and patients got better in half the time. What was standard and repeatable was optimized with software; what was non-standard and unpredictable was better addressed with professional human judgment.

This form of healthcare has spread around the world because it is both auditable and accountable. The data entry captures costs, but the freedom given to nurses ensures personal responsibility – something lost when blindly following predetermined schedules. The team structure isn’t incidental; it allows nurses to learn from each other, to discuss and debate options, possibilities and new ideas. Instead of being only as good as the instructions they receive, each nurse retains the capacity to learn, grow and share the value of their insights. But most important of all, they own the choices that they make. Such transparency builds trust, forging a fruitful collaboration between technology and the people who build and use it.

The world needs cohesion

This delicate balance is crucial to the public acceptance of emerging technologies. The essence of a good decision lies not just in what it determines but in how it is made, by whom and whether those at the receiving end regard the process as fair and legitimate. I might not like a new strategy but I’m more willing to go along with it when it can be explained by people I have reason to trust. That standard isn’t met by software that chooses, for example, which teachers to fire, which children to protect or which prisoners get parole. Artificial intelligence systems that nobody understands or can explain, or whose operating principles are protected as trade secrets, sacrifice for so-called efficiency the accountability, trust and legitimacy of the people who use them1. This has profound, long term consequences.

“The antidote is not to program people out, but to involve them more. In all the excitement about data and technology, it’s vital to remember that business and institutions don’t flourish where society fails.”

Earlier this year, in its Global Risk Report, the World Economic Forum identified the major risks facing the world today2. The first three related to the climate. The fourth was global cohesion erosion: an awkward phrase that captures the danger of society falling apart when people don’t feel included or able to participate. The antidote is not to program people out, but to involve them more. In all the excitement about data and technology, it’s vital to remember that business and institutions don’t flourish where society fails; both have a deep vested interest in a strong social fabric. The point of doctors and lawyers and teachers is not to eliminate them for efficiency but to work with them, with all of us, as unique and trusted sources of insight, judgment and legitimacy. Even in the face of uncertainty, that is what produces societies which can be both resilient and robust.

References

1 See Cathy O’Neil, Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (Penguin 2017) and Virginia Eubanks, Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor (Picador 2019).

2 https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2022.pdf

About the author

Margaret Heffernan is a Professor of Practice at the University of Bath, Lead Faculty for the Forward Institute’s Responsible Leadership Programme and, through Merryck & Co., mentors CEOs and senior executives of major global organizations. She holds an honorary doctorate from the University of Bath and continues to write for the Financial Times and the Huffington Post.

She is the author of six books (her third, Willful Blindness: Why We Ignore the Obvious at our Peril), was named one of the most important business books of the decade by the Financial Times) and her TED talks have been seen by over twelve million people. Her most recent book, Uncharted: How to Map the Future Together was published in 2020.